Dear reader, IP Draughts needs your help with some research. He has volunteered to give a short talk on the differences (if any) between an intellectual property licence and a covenant not to sue. The talk will be held at the London offices of Olswang on Tuesday 19 February at 5pm. Registration details here. IP Draughts is sure that the readers of this blog will be able to shed light on this puzzling subject.

Dear reader, IP Draughts needs your help with some research. He has volunteered to give a short talk on the differences (if any) between an intellectual property licence and a covenant not to sue. The talk will be held at the London offices of Olswang on Tuesday 19 February at 5pm. Registration details here. IP Draughts is sure that the readers of this blog will be able to shed light on this puzzling subject.

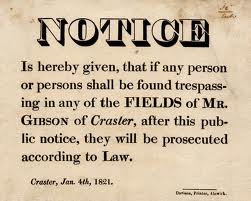

The expression covenant not to sue is sometimes seen in IP agreements, but when you examine the detailed wording of the clause in which the term appears, it often looks very much like a licence. The expression seems to originate in US agreements to settle IP litigation, but it has spread to some non-contentious agreements. Here is an example, taken from Drafting Patent License Agreements (Brunsvold et al, BNA Books, 6th edition at page 23):

Company A hereby covenants not to sue Company B under any patent listed in Exhibit A for infringement based upon any act by Company B of manufacture, use, sale, offer for sale or import that occurs after the effective date of this Agreement.

A traditional common law analysis is that a licence is merely a permission to do something which would otherwise infringe the licensor’s IP. A covenant (or promise) not to sue is just a negative way of saying the same thing as giving permission. Therefore a covenant not to sue is effectively the same as a non-exclusive licence.

Ah, but you’ve overlooked some important points, the critic may cry. A licence may carry with it some implied obligations, eg a warranty that the licensor owns the licensed IP, or an obligation to sue infringers. Moreover, a licence may be binding on subsequent owners of the IP, while a covenant not to sue is just a personal undertaking. Put another way, a licence is a kind of property right, while a covenant is merely a contractual obligation.

Ah, but you’ve overlooked some important points, the critic may cry. A licence may carry with it some implied obligations, eg a warranty that the licensor owns the licensed IP, or an obligation to sue infringers. Moreover, a licence may be binding on subsequent owners of the IP, while a covenant not to sue is just a personal undertaking. Put another way, a licence is a kind of property right, while a covenant is merely a contractual obligation.

Whether these criticisms are correct may depend partly on the law of the contract. English law may be at one end of the spectrum on this, as it is traditionally reluctant to imply terms into contracts. Countries that have a civil code may be more inclined to imply terms. There are also provisions in national IP laws that address the question of when a licence is binding on subsequent owners of the IP.

Sometimes, these issues are addressed by including additional wording in the clause. The sentence quoted above is followed in the book by two further sentences:

Company A hereby represents that it owns full legal and equitable title to each patent listed in Exhibit A. Company A further promises to impose the covenant of this paragraph on any third party to whom Company A may assign a patent listed in Exhibit A.

IP Draughts has seen wording that goes further than this, and states that any purported assignment of the patents without imposing the covenant on the new owner will be void. He is very doubtful as to whether such a provision would be effective under many countries’ laws.

A further issue of interpretation is whether the beneficiary of the covenant can assign the benefit to someone else. Similar questions arise in relation to a licensee’s ability to assign his licence.

A further issue of interpretation is whether the beneficiary of the covenant can assign the benefit to someone else. Similar questions arise in relation to a licensee’s ability to assign his licence.

On the question of whether a licence is an item of property, English law takes the approach that a licence is merely a contractual right, but it seems that US law may take a different approach, which may be an additional reason for distinguishing between licences and covenants. See this discussion (particularly the readers’ comments) from a few years ago on Ken Adams’ former blog.

As well as these general points, it seems that there are some specific issues in relation to the use of covenants not to sue in US litigation. First, it seems to be an established practice in the USA for a party that is engaged in IP litigation and who wants to stop the litigation (and thereby avoid an adverse decision), to give a covenant not to sue to the defendant. US courts have held that, if drafted widely enough, such a covenant makes the litigation “moot” and brings the litigation to an end. The recent decision of the US Supreme Court in the Nike case confirms this point.

This line of case law is important for IP litigators but doesn’t seem to be relevant to the question of whether a covenant is the same as a licence. More relevant on this point is a recent US case, in re Spansion, which was reported on the PatentlyO blog. An issue in that case was whether a covenant not to sue was a licence for the purpose of US insolvency legislation that allows an IP licensee to keep his licence following the insolvency of the licensor. As reported by PatentlyO, the Third Circuit decided that a covenant not to sue was the same as a licence, and quoted earlier US case law to this effect:

“[A] license … [is] a mere waiver of the right to sue by the patentee.” De Forest Radio Tel. & Tel. Co. v. United States, 273 U.S. 236, 242 (1927). A license need not be a formal grant, but is instead a “consent[ ] to [the] use of the patent in making or using it, or selling it … and a defense to an action for a tort.” Id. The Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit explained that the inquiry focuses on what the agreement authorizes, not whether the language is couched in terms of a license or a covenant not to sue; effectively the two are equivalent. TransCore, LP v. Elec. Transaction Consultants Corp., 563 F.3d 1271 (Fed. Cir. 2009).

IP Draughts is left confused by this maelstrom of conflicting usage and authority. The expression covenant not to sue seems artificial – a lawyer’s construct. The word licence is more straightforward and understandable.

IP Draughts is left confused by this maelstrom of conflicting usage and authority. The expression covenant not to sue seems artificial – a lawyer’s construct. The word licence is more straightforward and understandable.

Has IP Draughts identified the main issues that arise on this subject, and is this summary reasonably accurate? Please provide any comments you feel are appropriate to increase IP Draughts’ understanding.

Reblogged this on IP Draughts and commented:

Golden oldie number 3 – this subject prompts much discussion!

Hi Mark – A little late to the discussion, but I came upon this post while researching whether covenants not to sue transfer with a patent in the US. Most articles I’ve read seem to say they do not, yet I’ve been unable to locate any specific case law on the subject. In your research for your talk did you ever come upon a case that sheds light on the matter? Any assistance is greatly appreciated.

Cheers,

Daniel

Daniel, I don’t recall any specific discussion of this point. In the UK, protection of the licensee on sale of the patent generally comes from registering the licence, so the crunch question would be whether you could persuade the Patent Office to register a covenant, or indeed whether the Covenantee would cooperate. My sense is that one reason for calling it a covenant and not a licence is to try to avoid it being binding on future owners. If I were a judge I would want a lot of persuading before agreeing that a covenant runs with the patent.

Thanks, Pat. Good to get your thoughts. I managed to briefly cover these points, other than licensee estoppel, in my talk, and quoted from Transcore and Spansion (and also Yums v Nike in the Supreme Court, although this doesn’t have any bearing on the licence/covenant distinction). For non-contentious IP lawyers, I think the chief, potential differences between a licence and a covenant are whether a covenant (a) has any implied terms, and (b) is binding on subsequent owners of the IP. The answer to this will vary from jurisdiction to jurisdiction.

PR?

I have taken a licence = you have a right.

You have covenanted not to sue = your claim has no foundation.

Which looks better to the world?

Mmm… that may be right for press releases, but for contracts I want to exclude all PR and have clear, accurate, emotion-free language that sets out the parties’ rights and obligations and fits within the framework of applicable law.

I would have to check with the revenue recognition experts, but perhaps another factor in using a covenant not to sue from the perspective of the IP holder is that the entire revenue from the deal could be recognized immediately, whereas revenues from a royalty (even if prepaid) would likely have to be recognized over a period of time such as the term of the license grant.

Another interesting angle! Thanks Chuck.

Hi Mark

Extremely interesting blog. I wonder how an English court would look at a covenant not to sue in the context of assigning IPR with “full title guarantee”. Do you think a covenant not to sue amounts to an “interest” in the property?

Piers

Thanks, Piers. My view is that traditional English analysis says no, as it would with a licence. But I am starting to question this, after reading some of the US analysis.

I should mention a helpful response I received on Twitter from https://twitter.com/devlinhartline. He pointed me to an academic article on this subject, in the context of US copyright law, at http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2010853

Mark, I think the covenant not to sue formulation is sometimes used in commercial agreements in order to obscure the fact that some kind of license is indeed being granted.

A covenant not to sue might be the “compromise” the promisor makes acceding to the following kind of negotiating ask: “look, we get that you need to own what you build on top of our platform, and we are going to concede the point; but be reasonable and give us a corresponding assurance that you won’t turn your ownership against us.”

Couched as a peace treaty, a promise to not go on the offensive, the party making the covenant not to sue can lose sight of the fact that it has just negotiated a cross-license.

This is a trick, of course, and not a kind one. One might place it in the catalog of sharp dealing, alongside the infamous “residuals clause” (a kind of trade secret license).

Thanks, Bill, that is useful. Another tricksy reason for including a covenant instead of a licence might be where the licensor has previously entered into a non-exclusive licence agreement that includes a “most favoured licensee” clause. Some licensors might try to avoid the impact of such a clause by not licensing a third party (ie on better terms than are in the licence agreement) but instead covenanting not to sue the third party. I doubt whether that would get around the MFL clause under English law.

Mark: I agree that in semantic terms, granting a license is simpler and clearer than assuming an obligation not to sue. But I neglected to address this wrinkle in MSCD3. 😦 Ah, there’s always MSCD4 …

By the way, I revisited granting language in the following 2011 blog post: http://www.koncision.com/revisiting-license-granting-language/.

Ken

Thanks, Ken. Your comments in the 2011 post make me think that a licence is, in common sense terms, a grant of a set of “rights” and more than just a promise not to sue.

Dear Mark,

Might be interesting for you – Case C 376/11 – codified EU law. One issue therefore is whether anobligation is a contract for services or a license of IP. From this decision a licensor must be in a position to grant the use of something potentially forbidden by the IP right. The contract not to sue could be made with respect to IP one does not own – one could promise never to acquire the IP or if one did acquire it not to sue. A license can only be given on something you own. So a covenant not to sue is potentially broader in scope.

32 Although it is stated in the second subparagraph of Article 10(1) of Regulation No 874/2004 that the words ‘prior rights’ are to be understood to include, inter alia, registered national and Community trade marks, the word ‘licensee’ is not defined in that regulation. Nor is there any express reference in that regulation to the law of the Member States as regards such a definition.

33 The Court has consistently held that the need for a uniform application of European Union law and the principle of equality require that the terms of a provision of European Union law which makes no express reference to the law of the Member States for the purpose of determining its meaning and scope must normally be given an independent and uniform interpretation throughout the European Union; that interpretation must take into account the context of the provision and the objective of the relevant legislation (see, inter alia, Case 327/82 Ekro [1984] ECR 107, paragraph 11; Case C 287/98 Linster [2000] ECR I 6917, paragraph 43; and Case C 190/10 Génesis [2012] ECR I 0000, paragraph 40). 34 Furthermore, an implementing regulation must, if possible, be given an interpretation consistent with the basic regulation (Case C 90/92 Dr Tretter [1993] ECR I 3569, paragraph 11, and Case C 32/00 P Commission v Boehringer [2002] ECR I 1917, paragraph 53).

47 Consequently, it must be concluded that, by granting a licence, the proprietor of a trade mark confers on the licensee, within the limits set by the clauses of the licensing contract, the right to use that mark for the purposes falling within the area of the exclusive rights conferred by that mark, that is to say, the commercial use of that mark in a manner consistent with its functions, in particular the essential function of guaranteeing to consumers the origin of the goods or services concerned.

48 In the second place, the Court has had occasion, in Case C 533/07 Falco Privatstiftung and Rabitsch [2009] ECR I 3327, to examine the differences between a contract for services and a licence agreement in intellectual property law. It held, in paragraphs 29 and 30 of its judgment in that case, that, whereas the concept of service implies, at the least, that the party who provides the service carries out a particular activity in return for remuneration, it cannot be inferred from a contract under which the owner of an intellectual property right grants its contractual partner the right to use that right in return for remuneration that such an activity is involved. Kind regards,

William Bird

Patentive Prinz-Georg-Strasse 91 D-40479 Düsseldorf Germany

William Bird mobile +32 (0)468239777 Ariane Bird mobile +32 (0)471735350 Fax +49 (0)211 26 00 6 599

NOTICE: This email may contain confidential or privileged information intended for the addressee only. If you are not the addressee, be aware that any disclosure, copying, distribution, or use of the information is prohibited. If you have received this email in error, please call us at one of the telephone numbers above. Any legal advice expressed in this message is being delivered to you solely for your use in connection with the matters addressed herein and may not be relied upon by any other person or entity or used for any other purpose without our prior written consent.

Thanks, William. Interesting.

I have recently been pondering the same question, and wondered whether the licensor of an exclusive licence is in breach of that licence if it enters into a covenant not to sue in favour of a third party. I wondered if this was how it arose. Would this then stop the exclusive licensee bringing a claim against the third party?

Chris, I wonder if the answer depends partly on whether the licensor has any obligations to sue infringers? And also whether the covenant carries with it any obligation on the licensor to stop the exclusive licensee from suing (in jurisdictions where an exclusive licensee can sue in his own name)?

This also makes me wonder whether exclusivity has much meaning if the licensor does not accept an obligation to sue infringers or allow his licensee to do so.

I am late to blogging and late for your speech, but I found your discussion of covenants not to sue interesting. In the US, I believe the construct often was used by parties to hard-fought litigation who wanted to settle without any implication of validity of the patent that was litigated. While not true, defendants felt taking a license gave more credibility to the patent than justified and preferred a covenant. Also, a covenant was perceived to avoid the no challenge provision implicit in every license (licrensee estoppel) pre-Lear. Covenants were used where there was some question as to the grantor’s ownership interest in the patent, much like a quit claim. Covenants also were used to avoid patent exhaustion, but that rationale died with the Federal Circuit’s Transcore decision.which held that a covenant is equivalent to a license for purposes of patent exhaustion. The Federal Circuit’s decisions in Hilgraeve, Transcore and Spansion bring covenants very close to licenses, although there is no holding that covenants are binding on assignees of the patents. Even there, if the assignee was aware of the covenant, equity might apply. Covenants may eventually disappear as a distinction without a difference.